Front Lever Progression | A Comprehensive Guide

Disclosure: This article may contain affilitate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Key Takeaways

- Find the hardest progression you can hold for 8-20 seconds.

- Train using the 'Sweet Spot' on Steven Low's Isometric Table 2-3 times a week.

- Once you can hold that progression for 3x20s, use a harder progression.

- If you plateau or get stuck between two progressions, use one of the alternative progressions.

- Use the Worked Out Fitness workout tracking system to easily track your progress.

Overview

- About Me

- Progressions

- Optimal Sets and Hold Times

- Alternative Progressions

- Developing Your Training Plan

- Height, Weight, and Difficulty

- Tracking Your Progress

About Me

I am a front lever enthusiast. Ever since I got into calisthenics, the front lever has been one of my favorite skills. It was also one of the hardest for me to achieve.

I'm a taller, heavy-ish guy (6'3" 200lbs), which makes any sort of lever based exercise (ie the front lever) more difficult. I had to start at the very beginning and work my way through all of the progressions. Holding my first full front lever was one of the most satisfying moments of my life.

I'd like to share what I learned along the way, as well as a straightforward yet flexible training plan to help you hold your first lever too. I'll also share the best bodyweight training guide I've found and some tools I developed to help track your progress.

Progressions: From Beginner to Full

In traditional weight training, changing the difficulty of whatever exercise you're doing means choosing different dumbbells or putting some more plates on the bar. With the front lever, however, you change the difficulty by changing your body position.

Each progression in the section below gives its difficulty as a percentage of the full front lever. While this doesn't tell the whole story, it should give you an idea of how hard each position is compared to the others.

Foundational Strength (Beginner)

Even the tuck front lever requires a good amount of strength to hold. Most beginners will get to start here, just like I did.

Pulling Strength

Start with the hardest pulling exercise you can do for 3-4 sets of 5-8 reps. Once you can do 4 sets of 8 reps, try to move up to the next one.

- Inverted Row : A great foundational back exercise. If the standard version is too difficult to do 5 reps with, bend your knees rather than keeping your legs straight.

- Pull Up Negatives : Helps bridge the gap between full pull ups and rows. Doing just the eccentric portion has a similar training effect to doing a full pull up.

- Pull Up : Continues strengthening your pulling muscles. These can be weighted and you can continue to use them in conjunction with lever training.

Core Strength

Start with the hardest exercise that you can do for 3 sets of 10 seconds. Work up to 3 sets of 1 minute, then move up to the next hardest one.

- Plank : A great foundational core strength and stability exercise. Focus on keeping a neutral spine.

- Hollow Hold : The next step that pretty closely mimics the position that front lever puts you in. Make sure to keep your lower back touching the ground throughout the entire hold.

Tuck Levers (Novice/Intermediate)

-

Tuck:

(66.8%) As the full front lever, but tuck your knees to your chest. Try to maintain a neutral spine,

as this can help your form during later progressions.

-

Advanced Tuck:

(77.3%) Position your legs so that they are vertical with your knees bent 90 degrees.

One Leg and Straddle Levers (Intermediate/Advanced)

- Straddle: (76.5%-?) The straddle is a great progression tool for those with the mobility for it and might be the best way for some trainees to get all the way to the full front lever. By straddling wider or tighter, the difficulty can be changed. That being said, it can be somewhat difficult to track your width, which makes progressing not quite as straightforward. A wide straddle (135 degree angle between the legs) is about the same difficulty as an advanced tuck. A more moderate straddle (90 degree angle between the legs) is about the same difficulty as the one leg tuck.

-

One Leg Tuck:

(83.4%) Extend one leg straight while keeping the other one tucked to your chest. Alernate which leg is extended between sets.

-

One Leg Advanced Tuck:

(88.6%) Extend one leg straight while keeping the other one vertical with the knee bent 90 degrees. Alernate which leg is

extended between sets.

Half Lay and Full Levers (Advanced+)

-

Half Lay:

(89.6%) As the full front lever, but bend both legs 90 degrees at the knee.

-

Full:

(100%) Extend both legs straight and keep them in line with your torso. Arms should be kept straight, shoulder blades

pulled back and make sure not to pike at the hips.

Optimal Sets and Hold Times

Now that we've covered how to, in effect, add more weight, let's get into how many sets and how long your hold times should be.

In traditional weight training, different rep ranges produce different adaptations. For example, a set done with heavier weight and fewer reps is better for developing strength, while a set done with lighter weight and more reps is better for developing size and muscular endurance.

The same principle is true with the front lever and hold times. You'll want to do a harder progression for less hold time to develop strength or an easier progression with a longer hold time to develop size and muscular endurance. The hold time ranges for different adaptations are:

- Strength: 10 seconds or less

- Strength and Hypertrophy: 10 to 30 seconds

- Hypertrophy and Muscular Endurance: 30+ seconds

The different adaptations produced by the hold time ranges are due to your body's energy systems and types of muscle fibers. For example, your ATP-CP energy system is responsible for fuelling high intensity but short duration efforts. It is usually depleted after about 10 seconds after which the anaerobic system provides most of the energy.

Since your primary goal is likely achieving a front lever, you'll want to focus on developing strength. This means training a challenging progression for shorter hold times.

That being said, you also don't want to train at too high of an intensity. This increases your risk of injuries and makes it difficult to get the necessary volume in a reasonable amount of time.

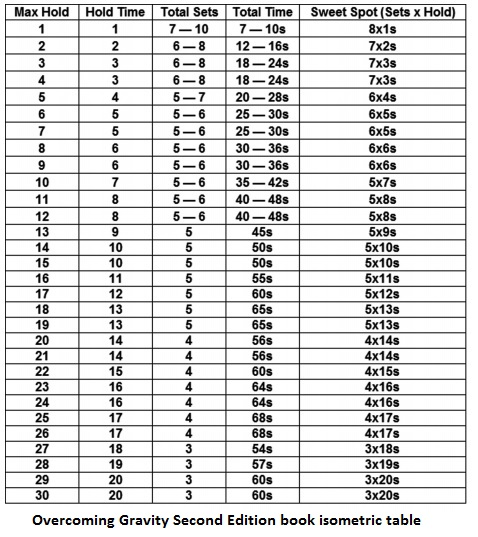

This brings us to Steven Low's isometric table. Steven Low, the author of Overcoming Gravity, created this table that outlines the optimal sets and hold time based on how long you can hold the position for.

While you can certainly use the whole table, I've found the optimal intensity to be a progression you can hold for between 8-20 seconds. This keeps the focus on strength, while not going too intense.

So, to find your optimal sets and hold times, figure out the most challenging progression you can hold for 10-20 seconds. Then, based on your max hold of that position, simply use the sets and hold times given in the Sweet Spot column.

If you find this table to be as helpful as I did, Steven has a whole book, Overcoming Gravity: A Systematic Approach to Gymnastics and Bodyweight Strength (Second Edition) filled with great information like this available on Amazon.

Alternative Progressions

While the standard progression exercises, sets, and hold times will work in most cases for most people, there are several options if you're not progressing with them.

Option #1: Dynamic Variations

There are three dynamic variations (listed from easiest to hardest):

- Negative: Start from an inverted hang and then slowly lower yourself to an active dead hang.

- Hold: While not a dynamic variation, this is where this fits in in terms of difficulty.

- Row: From a front lever progression hold, pull yourself up to the bar by bending your arms. Be sure to keep your body parallel to the ground.

- Raise: From an active dead hang, pull yourself to an inverted hang while keeping your arms straight.

These are useful in varying your training, bridging gaps between progression steps, and breaking through plateaus. For example, if you can't quite make the transition between to progression steps, you could do negatives of the harder one or try some raises of the easier one.

Sets and Reps

Since we're no longer dealing with isometric holds, here are the recommendations for each variation:

- Negatives: 3-6 sets of 3-10 second eccentrics. Each set is a single rep, trying to slowly lower yourself for up to 10 seconds. Try for 20-30 seconds total.

- Rows: 3-4 sets of 4-8 reps.

- Raises: 3-4 sets of 3-6 reps. Less reps than the rows because of the much larger range of motion.

Option #2: Transitional Progressions

Transitional progressions are great if you'd like to continue training with isometric holds, but the jump in difficulty from one progression to the next is too much. A transitional progression is simply a progression between two of the standard progression steps. For example, if going from tuck to advanced tuck is too challenging, position your legs between the two progression steps.

This is a great way to bridge the gap between the standard progression steps. However, try to be consistent in the transitional position you end up using. Otherwise progress can become difficult to track.

Option #3: Resistance Bands

With the right resistance bands, you could hypothetically train a full front lever immediately and simply decrease the strength of the band you're using as you progress. However, I find that resistance bands are more useful as a tool to help bridge the gap between progressions steps.

For example, the step from half lay to full is fairly large, so doing band assisted full front levers is a great way to make that transition.

Option #4: Other Pulling Exercises

Sometimes you just hit a plateau and doing more front lever training doesn't seem to be making any difference. In that case, there are many other exercises that will strengthen your back muscles and have good carry over to the front lever. Give them a try and come back to front lever training after a while.

- Pull ups

- Lat Pulldowns

- Inverted Rows

- Bent Over Rows

In terms of sets and reps, 3-4 sets of 5-8 reps works great. Be sure to add weight or use a harder progression once you can do 4 sets of 8 reps.

Developing Your Training Plan

By this point, we've covered almost everything needed for achieving the front lever. Let's put it all together into a straightforward, but still flexible training plan.

Step 1: Identify Your Progression Step

Find the progression step you can hold for 10-20 seconds. If you can't hold a tuck lever for 10 seconds yet, no worries. The Foundational Strength section has you covered.

Step 2: Determine How Frequently To Train

For most people, training 2 to 3 times each week is ideal. Be sure to take at least one rest day in between sessions. This gives you time to recover while still providing frequent enough stimulus.

Step 3: Making Progress

Try to do a little better every session. For example, if you held your advanced tuck for 5 sets of 8 second holds last workout, try to do 4 sets of 8 seconds and 1 set of 9 seconds.

Work your way on up through the 'Sweet Spot' column with the same progression step. Once you can hold a progression step for 4 sets of 15 seconds, test your max hold on the next progression step. If you can hold it for at least 10 seconds, start the process over with the new, more challenging progression step.

If you can't quite hold it for 10 seconds, use one of the alternative progressions or keep working your way up the 'Sweet Spot' column until you can do 3 sets of 20 seconds.

Injuries

A huge caveat here is injuries. I myself am very guilty of trying to do more even though my elbow or shoulder hurts a bit. Let me tell you, making progress one session is not worth the risk of needing to take weeks off to recover from an injury.

Step 4: As Part of Balanced Strength Program

If you're looking to integrate the front lever into another strength program, it can take the place of any upper body pulling exercise.

If you're not training it as part of another program, I would recommend also training some sort of upper body pushing exercise to keep your development balanced. Training for the planche or one arm push up pairs well with the front lever progression.

Height, Weight, and Difficulty

Simply put, the front lever is more difficult the taller and heavier you are.

To understand why this is, you need to understand what a moment is. A moment is the rotational force around a specific point and is found by multiplying a force and a distance. In this case:

- The specific point is your shoulders.

- The force is your weight.

- The distance is the length between your shoulders and your center of gravity.

So, (your weight) x (the distance between your shoulders and your center of gravity) = how hard it is to keep your body horizontal.

The weight is part is extremely straightforward. The heavier you are, the higher the weight part of the equation.

The height part isn't that much more complicated. Essentially, your center of gravity is further away from your shoulders the taller you are, increasing the distance part of the equation.

Also, as you may have noticed, each progression step simply changes where your center of gravity is. By moving your legs in closer to your shoulders, you're moving your center of gravity closer.

If you'd like to find the moment based on your height and weight for each of the progressions, check out my Lever Moment Calculator.

Tracking Your Progress

There are a lot of workout trackers out there, but I couldn't find one that would track my front lever progress very well. I knew I was getting better since I could hold harder progressions for longer, but I really wanted to know how much better.

So I made a workout tracking system that does just that. For every set you log, it calculates the maximum moment you could hold, taking into account your height, weight, progression, and hold time. These maximum moments are then visualized as part of your Fitness Dashboard so you can see your progress over time.

That's It

If you have any comments, questions or suggestions, please let me know by following the link for the contact page in the footer below.